The 18th biennial State of Forest Report (ISFR-2023) by the Forest Survey of India (FSI) found a marginal gain of 156 sq km in forest cover, and a sizable increase of 1,289 sq km in tree cover since 2021.

For the first time, India’s green cover has exceeded the 25% threshold with 8,27,357 sq km (25.17%) of the country now under forest (21.76%) and tree (3.41%) cover. Of this, 4,10,175 sq km is classified as dense forests.

Trees and forests

Tree patches smaller than 1 hectare do not count as forests, and have been measured separately by FSI as tree cover since 2001. The latest biennial cycle registered the sharpest growth in tree cover. From 3.04% in 2003, it had fallen to 2.76% in 2011, before rising to 2.91% in 2021. IFSR-2023 recorded a 0.5 percentage point jump in two years, with tree cover rising to 3.41%.

In comparison, India’s forest cover has increased by only 0.05 percentage points since 2021. This is consistent with the trend of diminishing growth since India’s forest cover crossed the 20% threshold at the turn of the millennium. Between 2003 and 2013, forest cover increased by 0.61 percentage points, from 20.62% to 21.23%. In the next 10 years, it grew by only 0.53 percentage points to 21.76%.

Forests within forest

Irrespective of land use or ownership, tree patches measuring 1 hectare or more with a minimum canopy cover of 10% are counted as forests in India. Areas with a canopy density of 40% and above are considered dense forests, and those with canopy density of 10-40% are open forests (OF). Since 2003, areas with at least 70% canopy density have been classified as very dense forests (VDF).

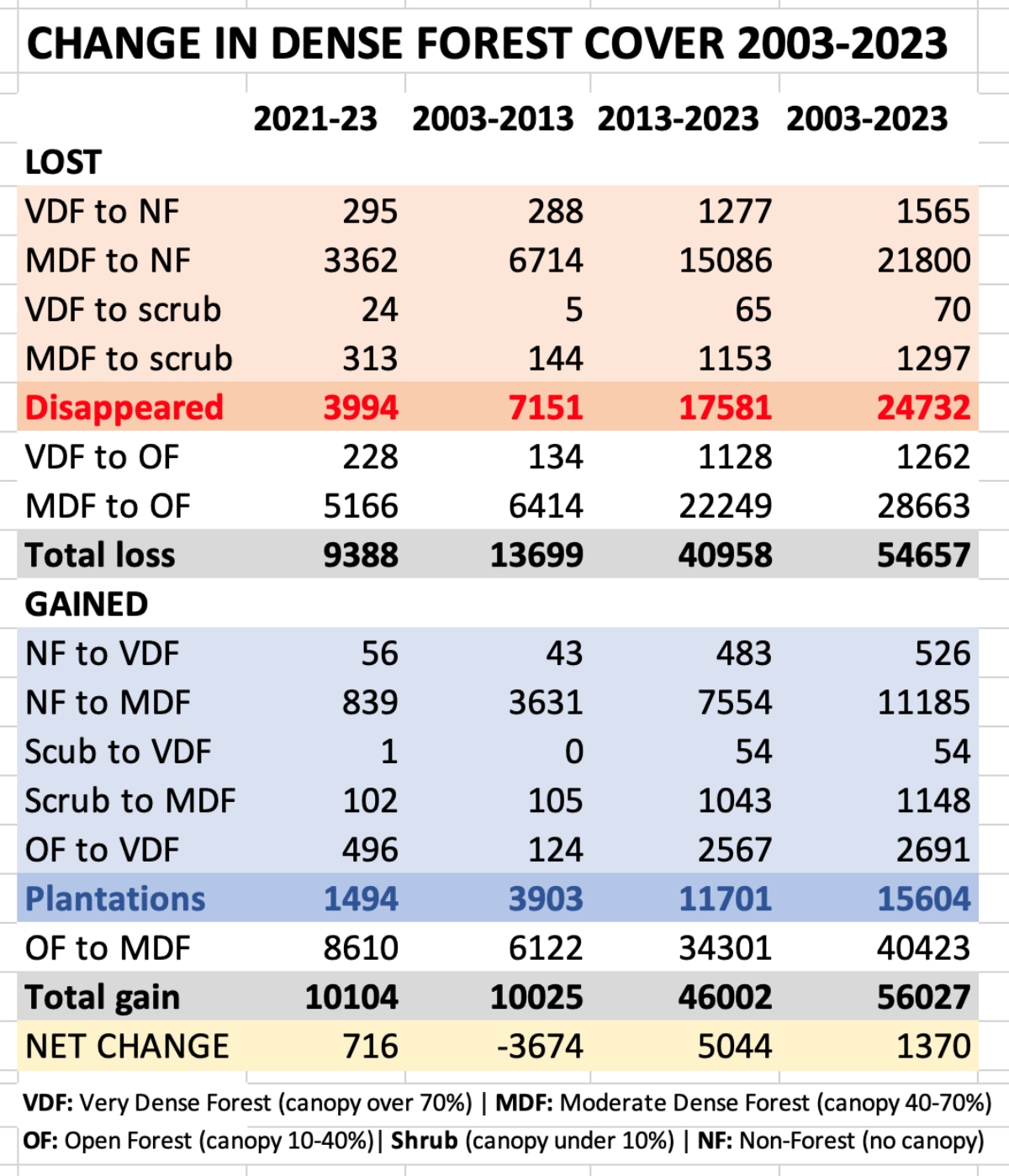

Depending on factors such as climate and biotic pressure, a forest can improve or degrade to the next density category — a VDF patch may thin to become a moderately dense forest (MDF) or an OF may get upgraded as an MDF — during a 2-year IFSR cycle. When a previously forested area is recorded as non-forest (NF) or shrub (below 10% canopy), it means that the forest has been wiped clean.

Plain aggregated data on the quantum of different forest types do not represent this dynamic process where natural forests transform, disappear, and are replaced by plantations that typically grow much faster. Since 2003, ISFRs have made available data on this “change matrix” which, stitched together, indicates the broad trends over two decades.

Forest balance sheet

ISFR-2023 shows that 3,913 sq km of dense forests — an area larger than Goa — have disappeared in India in just two years since 2021. (See chart). This is consistent with the worsening trend over the past two decades: 17,500 sq km of dense forests were wiped out between 2013 and 2023, while 7,151 sq km disappeared between 2003 and 2023.

Source: ISFR 2003-23

Source: ISFR 2003-23

Overall, India has witnessed the complete destruction of 24,651 sq km — more than 6.3% — of its dense forests in the two decades since 2003. As a single forest unit, that would be nearly half the size of Punjab.

The bulk of this loss has been offset by the rapid transformation of 15,530 sq km of non-forested or scantly forested land to dense or even very dense forests in successive two-year windows during 2003-2023. These are plantations, say experts, because natural forests do not grow this fast.

ISFR-2023 accounts for 1,420 sq km of plantations becoming dense forests since 2021. This again shows a downhill trend: areas under plantations-as-dense-forests are expanding as the disappearance of dense forests becomes routine.

Better management has helped large swaths of OFs become MDFs in the last decade. At the same time, plantations are supplementing these natural gains to keep the extent of India’s dense forest cover stable: the “change matrix” shows an increase of 1,370 sq km over 20 years. Of this, 716 sq km was gained in the 2021-23 cycle alone.

On paper, though, India’s dense forest cover has grown by 21,601 sq km — or 6% — during 2003-2023 due to a series of unexplained revisions of data presented in ISFR-2005, -2009, -2015 and -2021, adding a total of 20,232 sq km of dense forest to the inventory.

The implications

Under this opaque veneer of overall stability and growth in forest cover, the trend of steady replacement of natural dense forests with plantations has been criticised by experts.

Plantations usually have trees of the same age (and often the same species), are vulnerable to fire, pests and epidemics, and often act as a barrier to the regeneration of natural forests which are more biodiverse, perform a wider range of ecological functions, and support numerous species.

Old natural forests also stock a lot more carbon in their frame and in the soil. In 2018, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) flagged India’s assumption that plantations reach the carbon stock level of existing forests in just eight years.

Plantations are frequently promoted for their rapid growth which can achieve carbon targets faster. On the flip side, plantations are often harvested more readily, defeating climate goals in the long term.

Why should you buy our Subscription?

You want to be the smartest in the room.

You want access to our award-winning journalism.

You don’t want to be misled and misinformed.

Choose your subscription package