For India’s music lovers, the year 2024 has been a treat. From international music acts such as Jonas Brothers, Sting, Ed Sheeran, Maroon 5, Bryan Adams and Dua Lipa to its own Punjabi star Diljit Dosanjh, the year has been a series of concerts. With Coldplay’s Music of the Spheres World Tour, Ed Sheeran’s a seven-city tour that includes Shillong, and Mr. Big’s return to India after 15 years and even talks of a possible Eminem tour of India, 2025 also looks to be promising.

Data too appears to back this spurt in concerts. According to a year-end report by the online ticketing platform BookMyShow, 2024 saw “30,687 live events across 319 cities” — an 18 percent growth in India’s live entertainment consumption compared to the previous year. Significantly, the most dramatic growth — an astounding 682 percent — came from Tier-2 cities, with Kanpur, Shillong, and Gandhinagar emerging as strong markets for live events.

Dua Lipa performs at the Zomato Feeding India Concert (ZFIC) in Mumbai. (Photo credit: By special arrangement)

Dua Lipa performs at the Zomato Feeding India Concert (ZFIC) in Mumbai. (Photo credit: By special arrangement)

“The footfall at big-ticket concerts in India, such as those featuring artistes like Dua Lipa, Bryan Adams, and Diljit Dosanjh, has been substantial, and drawing over 30,000 concertgoers, filling stadiums and arenas to capacity,” a spokesperson from Zomato Live, a live entertainment platform, told The Indian Express.

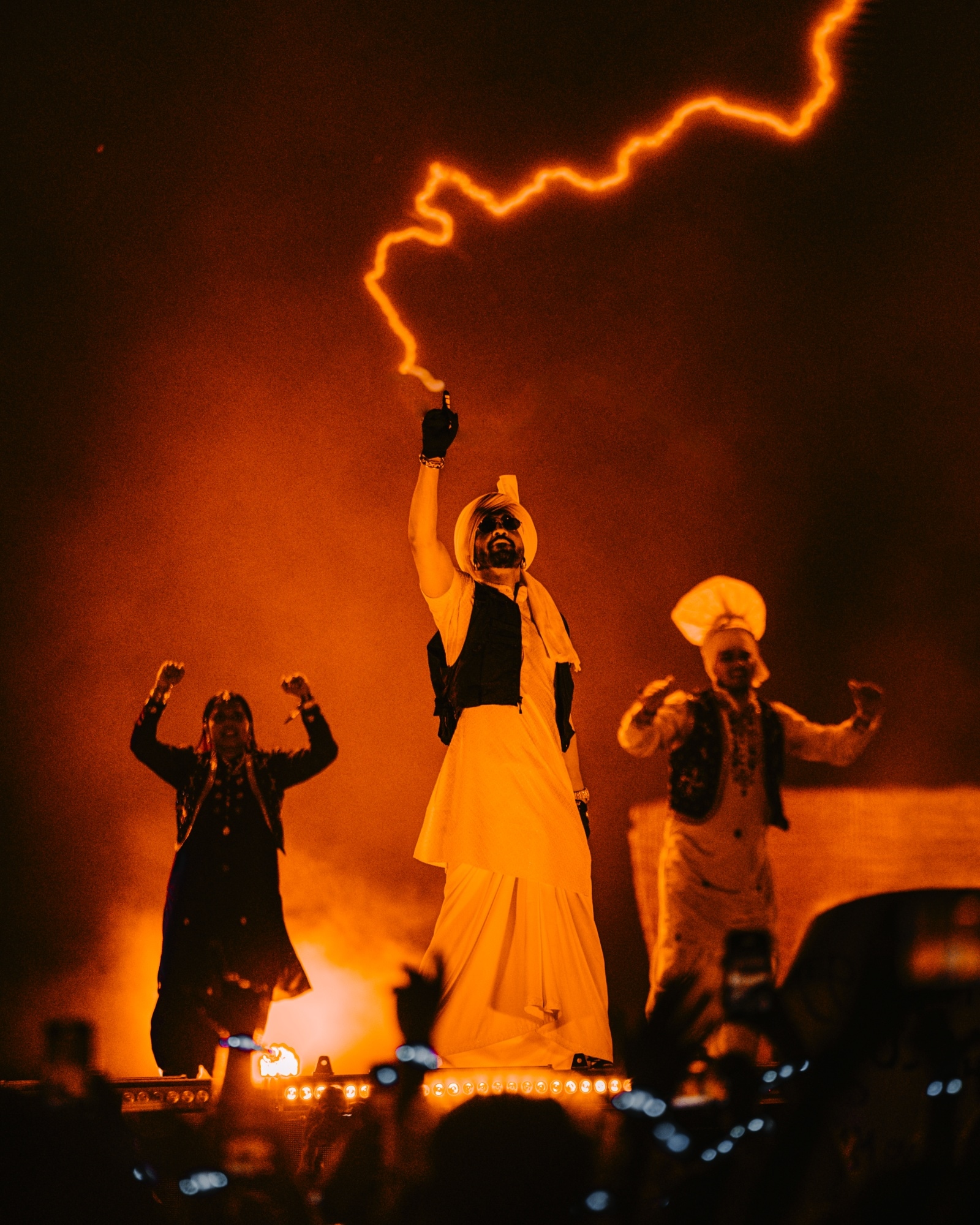

Diljit Dosanjh performs at a concert in Chandigarh. (Photo credit: By special arrangement)

Diljit Dosanjh performs at a concert in Chandigarh. (Photo credit: By special arrangement)

While cities such as Mumbai, Delhi, and Bangalore have been at the forefront of India’s burgeoning live music scene, the demand is also extending to Pune, Hyderabad, Kolkata, Ahmedabad, Chennai, Jaipur, Indore, and Goa.

“This growing demand is evident in the fact that over 50 percent of the ticket buyers for the Zomato Feeding India concert with Dua Lipa (in November) hailed from cities outside of Mumbai,” the spokesperson added.

Analysts believe that India’s billion-plus population, diverse musical tastes, growing appetite for live entertainment, and increasing disposable income is making it a hotspot for global artistes. According to Schubert Fernandes, a Mumbai-based publicist and indie artiste advisor, this concert boom was inevitable and would have happened earlier if not for the pandemic.

“An iconic and legendary band like U2 finally coming to India (in December 2019) would have opened doors for everyone else, but then COVID happened. Last year actually opened everything up for the country, and that’s also when Lollapalooza India (Music Festival) entered India, putting the country on a different league globally because it is arguably one of the top five concert franchises in the world,” he said.

But it’s not only the big names but also mid-level acts that appeal to the Indian musical taste.

“For instance, Karnivool, an Australian band, fills very small clubs back home, but the appetite for their music in India is incredible. Even niche acts like Animals as Leaders are surprised by the number of fans here,” said Yama Seth, head of talent at Level House — a management agency under Gurugram-based ticketing platform, SkillBox.

Another factor that could have added to the concert line up in India is the improved production standards in India. Anil Makhija, COO for live entertainment and venues at BookMyShow, cites the example of India’s first all-black-steel VerTech stage, used in the Maroon 5 concert at Mumbai’s Mahalaxmi Racecourse earlier this month. It was designed with a loading capacity of 50 tonnes—significantly higher than the typical 15-tonne capacity of most Indian stages.

Maroon 5 makes their India debut. (Photo credit: By special arrangement)

Maroon 5 makes their India debut. (Photo credit: By special arrangement)

“This upgrade meets the production demands of A-list international artistes who require advanced setups for their high-energy performances,” he said. “Infrastructure investments, coupled with evolving audience tastes, are cementing India’s position on the global entertainment map.”

He also credits digital platforms for Indian audiences’ exposure to diverse music and live entertainment. “In fact, India is the second-largest audio streaming market for many global artistes. This translates effectively to heightened on-ground demand for concerts by these artistes,” he said.

Experts also believe there’s also a shift in social currency, where attending high-profile events is now seen as a marker of cultural engagement — especially in the younger demographic. This is exemplified by the Indian audience’s willingness to spend on “live entertainment and immersive experiences”.

“A lot of entertainment spending has moved from films to live experiences. People are even planning vacations around concerts now,” Seth says.

But it’s not only music festivals in India – from Sunburn Goa to other niche ones like Mahindra Blues Festival, Percussion Fest, Magnetic Fields — that are gaining traction. There’s also a noticeable trend toward intimate performances in smaller venues that help create a close connection between artistes and audiences.

“For instance, Shan Vincent de Paul (a Tamil Canadian artiste), who first came to India in 2020 and performed at VH1 Supersonic during their debut tour, returned and performed at The Piano Man in Delhi and Bonobo in Bandra as part of their new IP (Intellectual Property), Big Artist Small Room,” Rani Kaur, who works with emerging and established indie artistes, said.

The target audience for concerts too are diverse, ranging from Gen Z and millennials to Gen X. For instance, it was the Gen Xers that flocked to the Bryan Adams concerts earlier this month. “Then, there are also casual listeners attending festivals for social experiences and corporate attendees leveraging concerts as networking opportunities,” Kaur said.

A long road ahead

During his Dil-Luminati concert in Chandigarh’s Sector-34 Exhibition Ground on December 14, Punjabi star Diljit Dosanjh highlighted a significant problem in holding large concerts in India – the lack of appropriate infrastructure.

“Here, we don’t have infrastructure for live shows,” he told his audience in Punjabi. “This is a source of big revenue; many people get work and are able to work here. I’ll try next time that the stage is at the centre so that you can be around it. Till this happens, I won’t do shows in India, that’s for sure.”

Dosanjh’s remarks, coupled with a LinkedIn post of how a concertgoer — a seasoned media and entertainment professional who’s diabetic – “peed his pants” due to inadequate washroom facilities, reignited a debate on how India lacks venues specifically designed for live performances, leading organisers to use spaces originally built for other purposes, such as sports stadiums.

This becomes significant especially given the distances people travel to attend concerts. Data from BookMyShow shows that in 2024, 4.77 lakh fans travelled outside their cities to attend live music events.

“Venues are a challenge,” admitted Fernandes. “Today, we are seeing high-calibre artistes performing at clubs that can accommodate only 100-400 standing guests because there’s no suitable venue. Music festivals are seeing international artistes expressing interest in performing in other cities, but venues remain a major hurdle.”

Nick Jonas from the Jonas Brothers at Lollapalooza India 2024. (Photo credit: By special arrangement)

Nick Jonas from the Jonas Brothers at Lollapalooza India 2024. (Photo credit: By special arrangement)

Globally, concerts are seen as an integral component to boost the economy and are often vied for. In March this year, Singapore became the only Southeast Asian country that hosted Taylor Swift’s The Eras Tour concerts, reportedly generating between US$260 million and US$375 million in tourism receipts.

Fernandes too believes that concerts have a huge economic potential in India — provided infrastructure keeps pace. He cited the example of how Trinamool Congress MP and spokesperson Saket Gokhale took to social media in November after his visit to Musicathon festival in Bir, Himachal Pradesh to ask musicians about how governments could help their art. Gokhale had also promised to take up the issue in Parliament.

Asked what the government can do, Fernandes said: “Build bigger infrastructure to host such concerts. Second thing is that the government should be a little more encouraging in terms of permissions”.

Why should you buy our Subscription?

You want to be the smartest in the room.

You want access to our award-winning journalism.

You don’t want to be misled and misinformed.

Choose your subscription package